import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

from sklearn.metrics import r2_score, mean_squared_error

import statsmodels.api as sm

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings('ignore')

# set visualisation style

sns.set_theme(style="whitegrid")

plt.rcParams['figure.figsize'] = (10, 6)Regression Fundamentals: Implementing Linear Regression

In the previous session, we explored what linear regression is, how it works conceptually, and why it’s such a powerful tool. We saw how regression finds the line of best fit by minimising prediction errors, and we understood the core components: intercepts, slopes, and residuals.

Now it’s time to put that theory into practice. In this session, we’ll learn how to actually build regression models in Python, interpret their outputs, check whether our models are valid, and generate insights from them.

We’ll cover two main approaches to regression in Python:

scikit-learn- Focused on prediction and machine learning workflows.statsmodels- Focused on statistical inference and hypothesis testing.

Let’s get started by loading our data and packages.

# load palmer penguins data

url = 'https://raw.githubusercontent.com/rfordatascience/tidytuesday/main/data/2025/2025-04-15/penguins.csv'

df = pd.read_csv(url)

# drop missing values for simplicity

df = df.dropna()Building Predictive Models Using Scikit-Learn

scikit-learn (sklearn) is Python’s most popular library for machine learning. Its regression tools are designed for building predictive models, and it is optimised for generalising well on new data.

Simple Linear Regression

A simple linear regression has one predictor variable. Let’s predict body mass from flipper length.

# prepare the data

# sklearn requires 2D arrays for X (predictors) and 1D arrays for y (outcome)

X = df[['flipper_len']] # double brackets create a dataframe

y = df['body_mass'] # single bracket creates a series

# create and fit the model

model = LinearRegression()

model.fit(X, y)

# get the intercept

intercept = model.intercept_

print(f"Intercept = {intercept:.2f}g")

# get the slope

slope = model.coef_[0]

print(f"Slope = {slope:.2f}g per mm")Intercept = -5872.09g

Slope = 50.15g per mmThe fitted model object contains everything we need: coefficients, predictions, and model performance metrics.

The intercept (\(\beta_0\)) = -5872.1g. The intercept tells us the predicted body mass when flipper length is 0mm. This intercept value is not meaningful because a flipper length of zero is implausible and ultimately nonsensical (if they have flippers, they must be longer than 0mm)1, but we need the intercept to fit the model.

The slope (\(\beta_1\)) = 50.2g/mm. The slope tells us that each additional mm increase in flipper length predicts ~50g increase in body mass.

Making Predictions

Once we have a fitted model, we can use it to predict body mass for any flipper length.

# predict body mass for all penguins in our dataset

y_pred = model.predict(X)

# add predictions to our dataframe

df['predicted_mass'] = y_pred

df['residual'] = df['body_mass'] - df['predicted_mass']

# look at some predictions

print("Sample predictions:")

print(df[['flipper_len', 'body_mass', 'predicted_mass', 'residual']].head(10))Sample predictions:

flipper_len body_mass predicted_mass residual

0 181.0 3750.0 3205.648453 544.351547

1 186.0 3800.0 3456.414782 343.585218

2 195.0 3250.0 3907.794176 -657.794176

4 193.0 3450.0 3807.487644 -357.487644

5 190.0 3650.0 3657.027846 -7.027846

6 181.0 3625.0 3205.648453 419.351547

7 195.0 4675.0 3907.794176 767.205824

12 182.0 3200.0 3255.801719 -55.801719

13 191.0 3800.0 3707.181112 92.818888

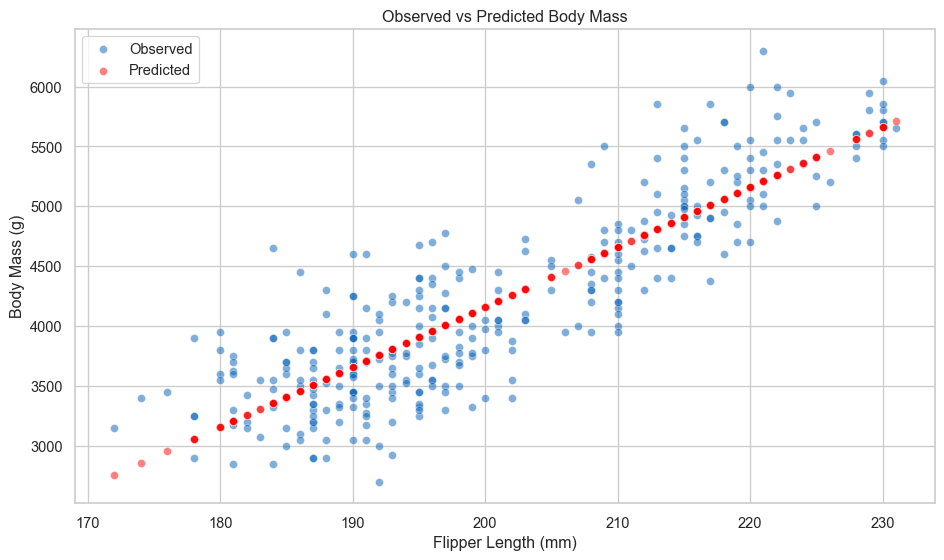

14 198.0 4400.0 4058.253974 341.746026We can plot the predictions too.

# plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

sns.scatterplot(data=df, x='flipper_len', y='body_mass', color='#005EB8', alpha=0.5, ax=ax, label='Observed')

sns.scatterplot(data=df, x='flipper_len', y='predicted_mass', color='red', alpha=0.5, ax=ax, label='Predicted')

ax.set_xlabel('Flipper Length (mm)')

ax.set_ylabel('Body Mass (g)')

ax.set_title('Observed vs Predicted Body Mass')

ax.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

We can also predict for new data.

# predict for hypothetical penguins

new_penguins = pd.DataFrame({

'flipper_len': [180, 200, 220]

})

new_predictions = model.predict(new_penguins)

print("\nPredictions for new penguins:")

for flipper, mass in zip(new_penguins['flipper_len'], new_predictions):

print(f"Flipper length: {flipper}mm --> Predicted mass: {mass:.0f}g")

Predictions for new penguins:

Flipper length: 180mm --> Predicted mass: 3155g

Flipper length: 200mm --> Predicted mass: 4159g

Flipper length: 220mm --> Predicted mass: 5162gModel Performance Metrics

An important part of predictive modelling is evaluation. We need to test how well our model is performing! sklearn provides a wide variety of metrics for assessing model performance. We will look at \(\text{R}^2\) and RMSE.

# r-squared: proportion of variance explained

r2 = r2_score(y, y_pred)

# root mean squared error: average prediction error in grams

rmse = np.sqrt(mean_squared_error(y, y_pred))The \(\text{R}^2\) = 0.76, which suggests that flipper length explains a significant amount of the variance in penguin body mass, while the RMSE indicates that the average prediction error is 392.16g. This means that predictions are, on average, off by 392.16g.

There is no rule of thumb or minimum threshold for good prediction error. It all depends on what you are trying to predict and what is needed for predictions to be useful. Another model trying to predict something completely different might have much larger prediction errors but this still be useful in context. It is always necessary to judge a model in context.

Multiple Linear Regression

Now let’s add more predictors. Multiple regression lets us understand the effect of each variable while controlling for the others.

# add bill length and bill depth as predictors

X_multi = df[['flipper_len', 'bill_len', 'bill_dep']]

y = df['body_mass']

# fit the model

model_multi = LinearRegression()

model_multi.fit(X_multi, y)

# extract coefficients

print("Multiple regression coefficients:")

print(f"Intercept: {model_multi.intercept_:.2f}g")

for name, coef in zip(X_multi.columns, model_multi.coef_):

print(f" {name}: {coef:.2f}g per unit")

# compare model performance

y_pred_multi = model_multi.predict(X_multi)

r2_multi = r2_score(y, y_pred_multi)

rmse_multi = np.sqrt(mean_squared_error(y, y_pred_multi))

print(f"\nModel comparison:")

print(f"Simple model (flipper only): R² = {r2:.3f}, RMSE = {rmse:.1f}g")

print(f"Multiple model (three vars): R² = {r2_multi:.3f}, RMSE = {rmse_multi:.1f}g")Multiple regression coefficients:

Intercept: -6445.48g

flipper_len: 50.76g per unit

bill_len: 3.29g per unit

bill_dep: 17.84g per unit

Model comparison:

Simple model (flipper only): R² = 0.762, RMSE = 392.2g

Multiple model (three vars): R² = 0.764, RMSE = 390.6gAdding bill measurements improves our model slightly. Each predictor contributes information beyond what the others provide.

Building Inferential Models Using Statsmodels

statsmodels is designed for statistical inference2. It provides detailed output about uncertainty, hypothesis tests, and model diagnostics. This is what you want when your goal is understanding relationships rather than pure prediction.

Adding predictors is straightforward with the formula interface.

# multiple regression with formula

model_sm = smf.ols('body_mass ~ flipper_len + bill_len + bill_dep', data=df).fit()

print(model_sm.summary()) OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: body_mass R-squared: 0.764

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.762

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 354.9

Date: Thu, 06 Nov 2025 Prob (F-statistic): 9.26e-103

Time: 13:30:25 Log-Likelihood: -2459.8

No. Observations: 333 AIC: 4928.

Df Residuals: 329 BIC: 4943.

Df Model: 3

Covariance Type: nonrobust

===============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Intercept -6445.4760 566.130 -11.385 0.000 -7559.167 -5331.785

flipper_len 50.7621 2.497 20.327 0.000 45.850 55.675

bill_len 3.2929 5.366 0.614 0.540 -7.263 13.849

bill_dep 17.8364 13.826 1.290 0.198 -9.362 45.035

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 5.596 Durbin-Watson: 1.982

Prob(Omnibus): 0.061 Jarque-Bera (JB): 5.469

Skew: 0.312 Prob(JB): 0.0649

Kurtosis: 3.068 Cond. No. 5.44e+03

==============================================================================

Notes:

[1] Standard Errors assume that the covariance matrix of the errors is correctly specified.

[2] The condition number is large, 5.44e+03. This might indicate that there are

strong multicollinearity or other numerical problems.The statsmodels summary is dense but incredibly informative. Here’s what matters most.

coef- The estimated effect size of each variable holding the others constantstd err- Uncertainty in the estimatet- Test statistic (coef / std err)P>|t|- p-value for null hypothesis that coefficient = 0[0.025, 0.975]- 95% confidence interval

Focus on effect sizes first, then uncertainty. The coefficient tells you the magnitude of the relationship. The confidence interval tells you how precisely we’ve estimated it. Don’t obsess over \(\text{R}^2\)3 or p-values. The most important part of the model is the coefficients.

The p-value is useful as a diagnostic, indicating whether you have enough data, but it doesn’t tell you whether the effect is meaningful or important.

We can also produce a simpler regression table, if the above is overwhelming.

# extract just the coefficients table

print(model_sm.summary().tables[1])===============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Intercept -6445.4760 566.130 -11.385 0.000 -7559.167 -5331.785

flipper_len 50.7621 2.497 20.327 0.000 45.850 55.675

bill_len 3.2929 5.366 0.614 0.540 -7.263 13.849

bill_dep 17.8364 13.826 1.290 0.198 -9.362 45.035

===============================================================================Styled Tables (Click to Expand)

For presentations and reports, we can create publication-ready tables.

from great_tables import GT, md, html

from great_tables import loc, style

# fit three models for comparison

model1 = smf.ols('body_mass ~ flipper_len', data=df).fit()

model2 = smf.ols('body_mass ~ flipper_len + bill_len + bill_dep', data=df).fit()

model3 = smf.ols('body_mass ~ flipper_len + bill_len + bill_dep + C(species)', data=df).fit()

# create a dataframe with model results

results_df = pd.DataFrame({

'Variable': ['Intercept', 'Flipper Length', 'Bill Length', 'Bill Depth',

'Chinstrap', 'Gentoo'],

'Model 1': [

f"{model1.params['Intercept']:.1f}",

f"{model1.params['flipper_len']:.2f}***",

'—', '—', '—', '—'

],

'Model 2': [

f"{model2.params['Intercept']:.1f}",

f"{model2.params['flipper_len']:.2f}***",

f"{model2.params['bill_len']:.2f}***",

f"{model2.params['bill_dep']:.2f}",

'—', '—'

],

'Model 3': [

f"{model3.params['Intercept']:.1f}",

f"{model3.params['flipper_len']:.2f}***",

f"{model3.params['bill_len']:.2f}***",

f"{model3.params['bill_dep']:.2f}**",

f"{model3.params['C(species)[T.Chinstrap]']:.1f}***",

f"{model3.params['C(species)[T.Gentoo]']:.1f}***"

]

})

# add model statistics

stats_df = pd.DataFrame({

'Variable': ['', 'N', 'R²', 'Adj. R²', 'AIC'],

'Model 1': ['', f"{int(model1.nobs)}", f"{model1.rsquared:.3f}",

f"{model1.rsquared_adj:.3f}", f"{model1.aic:.1f}"],

'Model 2': ['', f"{int(model2.nobs)}", f"{model2.rsquared:.3f}",

f"{model2.rsquared_adj:.3f}", f"{model2.aic:.1f}"],

'Model 3': ['', f"{int(model3.nobs)}", f"{model3.rsquared:.3f}",

f"{model3.rsquared_adj:.3f}", f"{model3.aic:.1f}"]

})

combined_df = pd.concat([results_df, stats_df], ignore_index=True)

# create styled table

table = (

GT(combined_df)

.tab_header(

title="Regression Models Predicting Penguin Body Mass",

subtitle="Coefficients with significance stars (* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001)"

)

.tab_spanner(

label="Model Specifications",

columns=['Model 1', 'Model 2', 'Model 3']

)

.tab_style(

style=style.text(weight="bold"),

locations=loc.body(rows=[6, 7, 8, 9, 10])

)

.tab_style(

style=style.borders(sides="top", weight="2px"),

locations=loc.body(rows=[6])

)

.cols_align(

align="center",

columns=['Model 1', 'Model 2', 'Model 3']

)

.cols_align(

align="left",

columns=['Variable']

)

)

table| Regression Models Predicting Penguin Body Mass | |||

| Coefficients with significance stars (* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001) | |||

| Variable | Model Specifications | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Intercept | -5872.1 | -6445.5 | -4282.1 |

| Flipper Length | 50.15*** | 50.76*** | 20.23*** |

| Bill Length | — | 3.29*** | 39.72*** |

| Bill Depth | — | 17.84 | 141.77** |

| Chinstrap | — | — | -496.8*** |

| Gentoo | — | — | 965.2*** |

| N | 333 | 333 | 333 |

| R² | 0.762 | 0.764 | 0.849 |

| Adj. R² | 0.761 | 0.762 | 0.847 |

| AIC | 4926.1 | 4927.6 | 4781.7 |

Adding Categorical Variables

statsmodels handles categorical variables automatically with the formula interface.

# add species as a categorical predictor

# statsmodels automatically creates dummy variables

model_species_sm = smf.ols('body_mass ~ flipper_len + bill_len + bill_dep + C(species)',

data=df).fit()

print(model_species_sm.summary()) OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: body_mass R-squared: 0.849

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.847

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 369.1

Date: Thu, 06 Nov 2025 Prob (F-statistic): 4.22e-132

Time: 13:30:25 Log-Likelihood: -2384.8

No. Observations: 333 AIC: 4782.

Df Residuals: 327 BIC: 4805.

Df Model: 5

Covariance Type: nonrobust

===========================================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Intercept -4282.0802 497.832 -8.601 0.000 -5261.438 -3302.723

C(species)[T.Chinstrap] -496.7583 82.469 -6.024 0.000 -658.995 -334.521

C(species)[T.Gentoo] 965.1983 141.770 6.808 0.000 686.301 1244.096

flipper_len 20.2264 3.135 6.452 0.000 14.059 26.394

bill_len 39.7184 7.227 5.496 0.000 25.501 53.936

bill_dep 141.7714 19.163 7.398 0.000 104.072 179.470

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 7.321 Durbin-Watson: 2.248

Prob(Omnibus): 0.026 Jarque-Bera (JB): 7.159

Skew: 0.348 Prob(JB): 0.0279

Kurtosis: 3.179 Cond. No. 6.01e+03

==============================================================================

Notes:

[1] Standard Errors assume that the covariance matrix of the errors is correctly specified.

[2] The condition number is large, 6.01e+03. This might indicate that there are

strong multicollinearity or other numerical problems.The C() wrapper tells statsmodels to treat species as categorical. The model automatically creates “dummy variables”, which splits the categorical variable into multiple columns, with each column being a binary variable representing a category (where the variable equals one when that category appears in the original column).

When creating the dummy variables, the model drops one category to use it as the reference category against which the other categories are compared. This means that coefficients for those categories tell us how much the outcome variable increases or decreases compared against the reference category that was dropped.

For example, the model specified above uses Adelie penguins as the reference category (it chooses by alphabetical order by default), and the coefficients represent the species effects relative to Adelie penguins.

print("\nSpecies effects relative to Adelie:")

for var in model_species_sm.params.index:

if 'species' in var:

coef = model_species_sm.params[var]

ci = model_species_sm.conf_int().loc[var]

species = var.split('[T.')[1].rstrip(']')

print(f"{species:12s}: {coef:7.0f}g heavier [{ci[0]:7.0f}, {ci[1]:7.0f}]")

Species effects relative to Adelie:

Chinstrap : -497g heavier [ -659, -335]

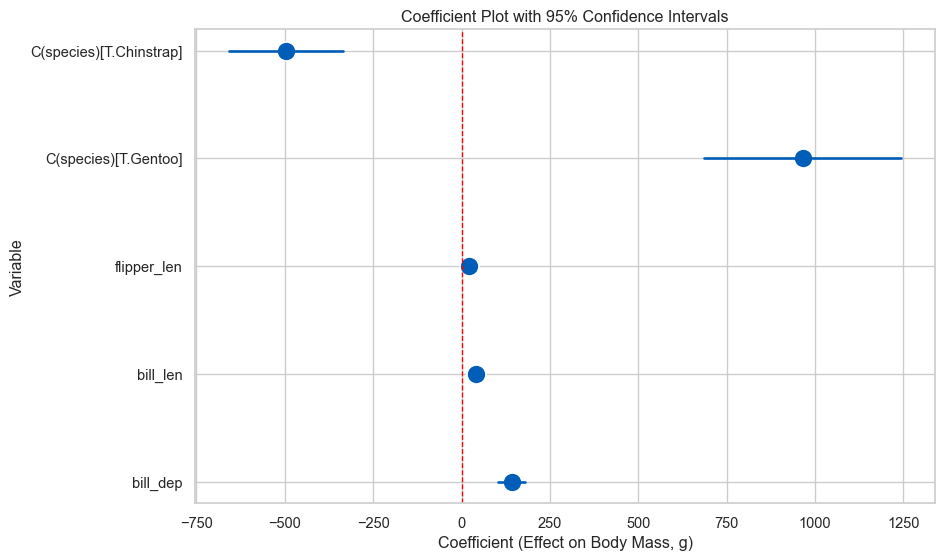

Gentoo : 965g heavier [ 686, 1244]Coefficient Plots

Coefficient plots show effect sizes and their uncertainty at a glance.

# extract coefficients and confidence intervals

coefs = model_species_sm.params.drop('Intercept')

conf_int = model_species_sm.conf_int().drop('Intercept')

# create dataframe for plotting

coef_data = pd.DataFrame({

'Variable': coefs.index,

'Coefficient': coefs.values,

'Lower': conf_int[0].values,

'Upper': conf_int[1].values

})

# plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

sns.scatterplot(data=coef_data, x='Coefficient', y='Variable', s=200,

color='#005EB8', ax=ax)

for idx, row in coef_data.iterrows():

ax.plot([row['Lower'], row['Upper']], [row['Variable'], row['Variable']],

color='#005EB8', linewidth=2)

ax.axvline(x=0, color='red', linestyle='--', linewidth=1)

ax.set_xlabel('Coefficient (Effect on Body Mass, g)')

ax.set_title('Coefficient Plot with 95% Confidence Intervals')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Variables whose CI doesn’t cross zero have effects distinguishable from zero. But remember: focus on effect sizes, not just significance!

Regression Assumptions and Diagnostics

Linear regression makes several assumptions. When these hold, OLS gives us the Best Linear Unbiased Estimator (BLUE). When they don’t, we need to either fix the problem4 or acknowledge the limitations.

The Gauss-Markov Theorem

Under certain conditions, OLS is BLUE:

- Linearity: The relationship between X and Y is linear

- Independence: Observations are independent of each other

- Homoscedasticity: Variance of errors is constant across X

- No perfect multicollinearity: Predictors aren’t perfectly correlated

- Exogeneity: Errors have mean zero (no systematic bias)

Additionally, for valid inference (confidence intervals, p-values), we need:

- Normality: Errors are normally distributed (or we have a large sample)

Let’s check these assumptions systematically.

Diagnostic Plots

We’ll create a set of diagnostic plots to check our assumptions. First, let’s fit a model to diagnose.

# fit our model with species

model = model_species_sm # use the statsmodels model from earlier

# get predictions and residuals

df['fitted'] = model.fittedvalues

df['residuals'] = model.resid

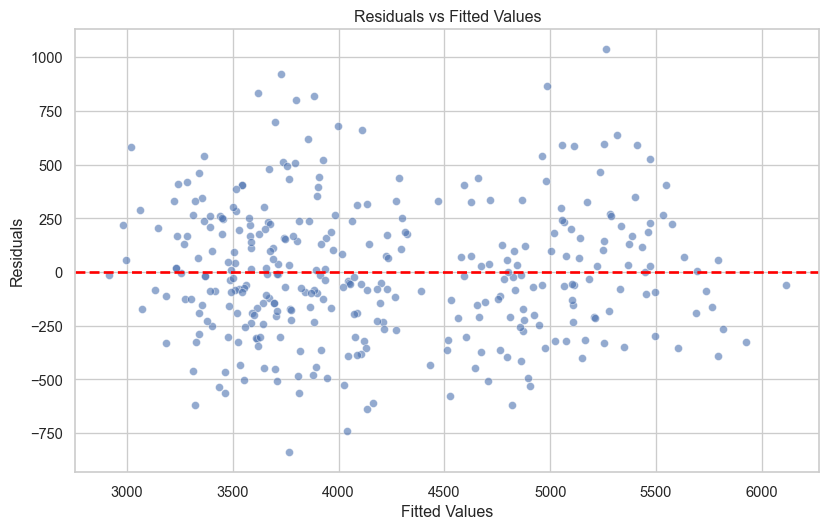

df['standardised_residuals'] = model.resid_pearson1. Residuals vs Fitted (Linearity & Homoscedasticity)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

sns.scatterplot(x=df['fitted'], y=df['residuals'], alpha=0.6, ax=ax)

ax.axhline(y=0, color='red', linestyle='--', linewidth=2)

ax.set_xlabel('Fitted Values')

ax.set_ylabel('Residuals')

ax.set_title('Residuals vs Fitted Values')

plt.show()

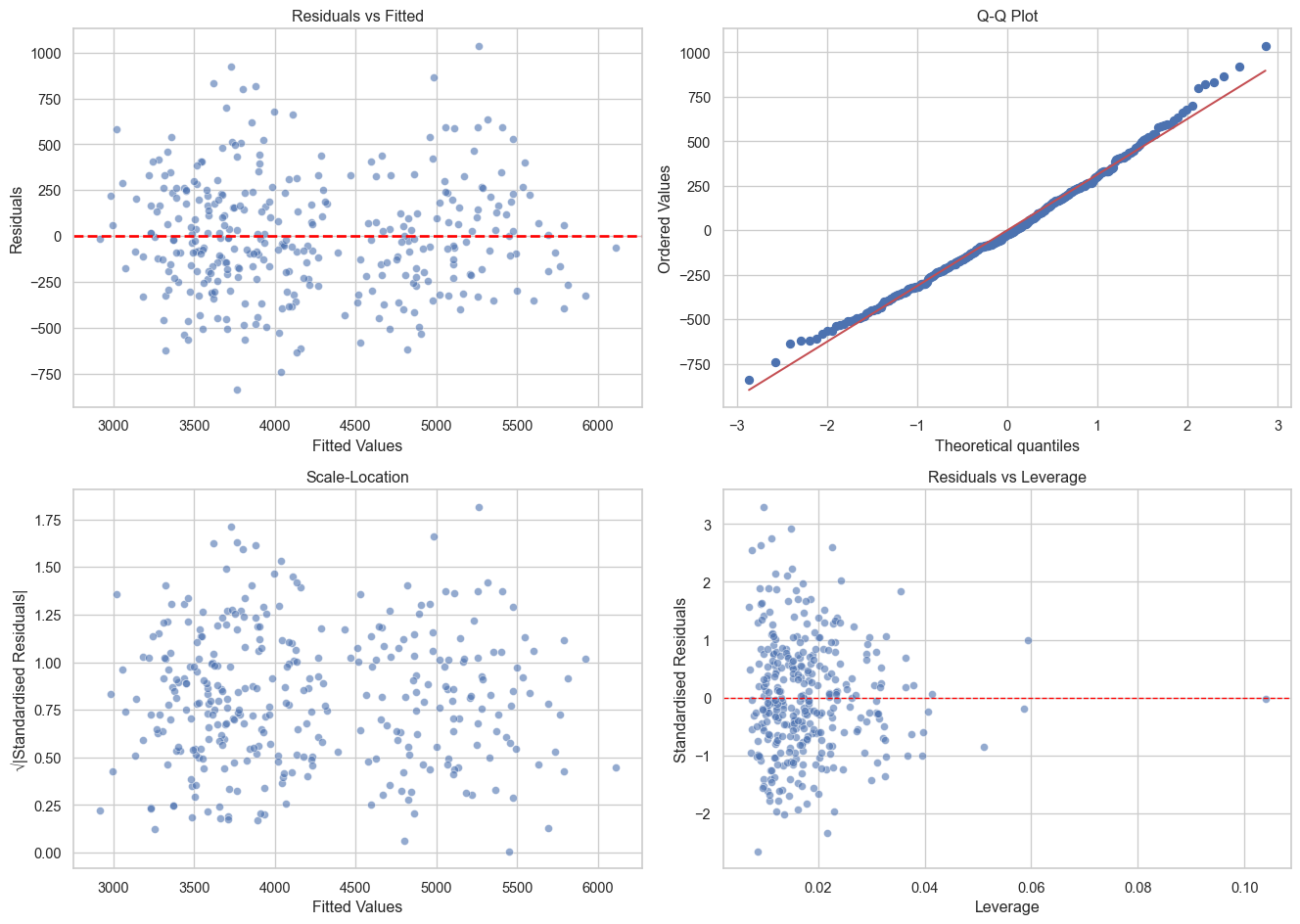

The observations should appear to be randomly scattered around zero, and the spread around zero should be constant across the range of fitted values. If you can see a pattern or trend, this suggests the linearity assumption is violated, and if the observations are funnel-shaped, this suggests that the homoscedasticity assumption is violated.

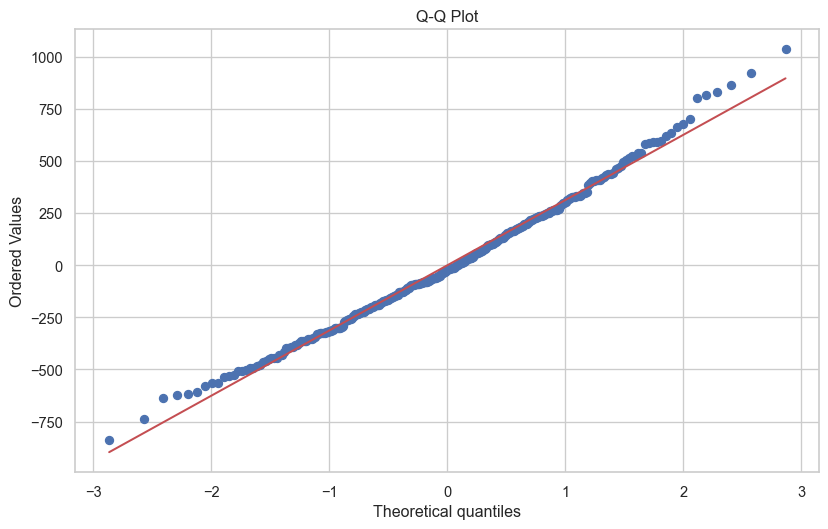

2. Q-Q Plot (Normality)

from scipy import stats

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

stats.probplot(df['residuals'], dist="norm", plot=ax)

ax.set_title('Q-Q Plot')

plt.show()

The closer to the red line, the better. However, some deviation is generally fine, and as sample size increases this becomes less of a concern. The very small deviations from the line above are not a cause for concern.

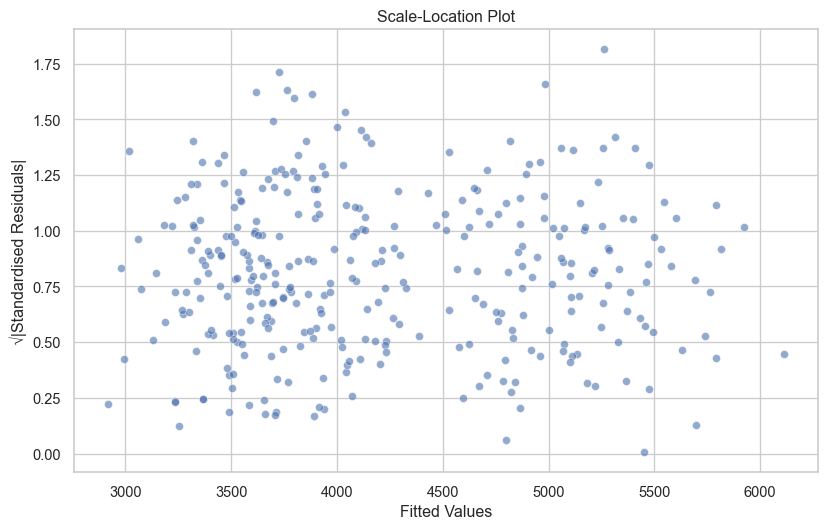

3. Scale-Location Plot (Homoscedasticity)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

sns.scatterplot(x=df['fitted'], y=np.sqrt(np.abs(df['standardised_residuals'])), alpha=0.6, ax=ax)

ax.set_xlabel('Fitted Values')

ax.set_ylabel('√|Standardised Residuals|')

ax.set_title('Scale-Location Plot')

plt.show()

If there is an observable trend or pattern in your Scale-Location plot, this indicates heteroscedasticity.

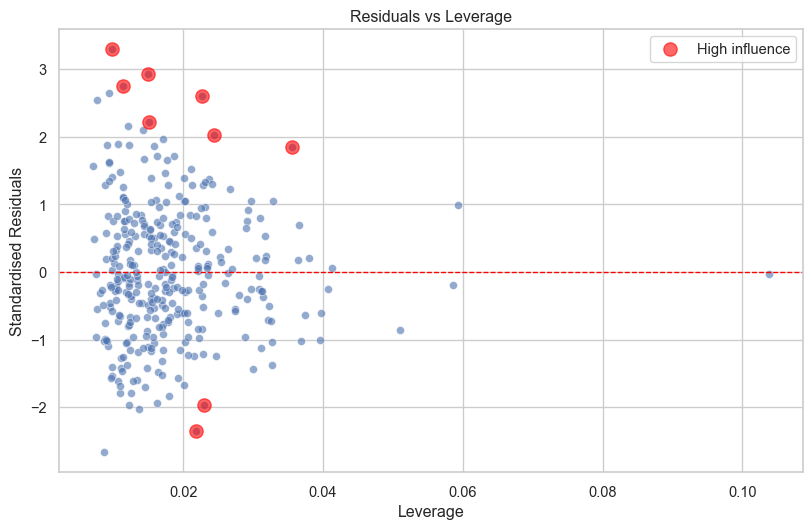

4. Residuals vs Leverage (Influential Points)

from statsmodels.stats.outliers_influence import OLSInfluence

influence = OLSInfluence(model)

leverage = influence.hat_matrix_diag

cooks_d = influence.cooks_distance[0]

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

sns.scatterplot(x=leverage, y=df['standardised_residuals'], alpha=0.6, ax=ax)

ax.axhline(y=0, color='red', linestyle='--', linewidth=1)

ax.set_xlabel('Leverage')

ax.set_ylabel('Standardised Residuals')

ax.set_title('Residuals vs Leverage')

# highlight high influence points

high_influence = cooks_d > 4/len(df)

if high_influence.any():

ax.scatter(leverage[high_influence], df['standardised_residuals'][high_influence],

color='red', s=100, alpha=0.6, label='High influence')

ax.legend()

plt.show()

Points that are significantly higher or lower than zero and with high leverage are potentially a problem.

However, I would caution against just removing outliers because they have a significant influence. If those outliers are real observations, should they really be discarded?

Quick Diagnostic Function (Click to Expand)

Let’s create a helper function to generate all diagnostic plots at once.

def plot_diagnostics(model, data=None):

"""

Create a 2x2 grid of diagnostic plots for a statsmodels regression model.

Parameters:

-----------

model : statsmodels regression model

A fitted statsmodels OLS model

data : pandas DataFrame, optional

The data used to fit the model (for some plot enhancements)

"""

# get residuals and fitted values

fitted = model.fittedvalues

residuals = model.resid

standardised_residuals = model.resid_pearson

# calculate leverage and influence

influence = OLSInfluence(model)

leverage = influence.hat_matrix_diag

# create 2x2 plot

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(14, 10))

# 1. residuals vs fitted

sns.scatterplot(x=fitted, y=residuals, alpha=0.6, ax=axes[0, 0])

axes[0, 0].axhline(y=0, color='red', linestyle='--', linewidth=2)

axes[0, 0].set_xlabel('Fitted Values')

axes[0, 0].set_ylabel('Residuals')

axes[0, 0].set_title('Residuals vs Fitted')

# 2. q-q plot

stats.probplot(residuals, dist="norm", plot=axes[0, 1])

axes[0, 1].set_title('Q-Q Plot')

# 3. scale-location

sns.scatterplot(x=fitted, y=np.sqrt(np.abs(standardised_residuals)), alpha=0.6, ax=axes[1, 0])

axes[1, 0].set_xlabel('Fitted Values')

axes[1, 0].set_ylabel('√|Standardised Residuals|')

axes[1, 0].set_title('Scale-Location')

# 4. residuals vs leverage

sns.scatterplot(x=leverage, y=standardised_residuals, alpha=0.6, ax=axes[1, 1])

axes[1, 1].axhline(y=0, color='red', linestyle='--', linewidth=1)

axes[1, 1].set_xlabel('Leverage')

axes[1, 1].set_ylabel('Standardised Residuals')

axes[1, 1].set_title('Residuals vs Leverage')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# use the function

plot_diagnostics(model_species_sm)

Checking for Multicollinearity

When predictors are highly correlated with each other, coefficient estimates become unstable. We can check this using Variance Inflation Factors (VIF).

from statsmodels.stats.outliers_influence import variance_inflation_factor

# calculate VIF for each predictor

# need to add constant for VIF calculation

X_with_const = sm.add_constant(df[['flipper_len', 'bill_len', 'bill_dep']])

vif_data = pd.DataFrame()

vif_data['Variable'] = X_with_const.columns

vif_data['VIF'] = [variance_inflation_factor(X_with_const.values, i)

for i in range(X_with_const.shape[1])]

print("Variance Inflation Factors:")

print(vif_data)Variance Inflation Factors:

Variable VIF

0 const 691.005294

1 flipper_len 2.633327

2 bill_len 1.850958

3 bill_dep 1.593411The rule of thumb:

- VIF of greater than five = No multicollinearity

- VIF of between five and ten = Moderate multicollinearity

- VIF greater than ten = High multicollinearity

What Happens When Assumptions Are Violated?

Understanding assumptions helps you know when you can bend or break the rules.

- Linearity - Coefficients are biased. Try transformations (log, polynomial) or non-linear models.

- Independence - Standard errors are wrong (usually too small). Use clustered standard errors or multilevel models.

- Homoscedasticity - Standard errors are wrong. Use robust standard errors (HC3, HC4). Predictions are still unbiased.

- Normality - With large samples, not a big problem due to central limit theorem. With small samples, confidence intervals may be wrong.

- Multicollinearity - Coefficients are unstable and hard to interpret, but predictions are fine. Remove or combine correlated predictors.

As you gain experience, you’ll learn when violations matter and when they don’t. For now, check diagnostics and flag any concerns.

Summary

sklearnfor prediction - Fast, consistent API for building models.statsmodelsfor inference - Detailed statistical output for understanding.- Assumptions matter - Check diagnostics, understand when violations are problematic.

- Effect sizes over p-values - Focus on what matters practically.

Linear regression is a powerful tool, and learning the principles of linear regression (thinking about predictions, uncertainty, assumptions, and interpretation) apply to much more complex models.

Footnotes

For explanatory models, it is generally best-practice to transform the data so that the intercept is meaningful. For example, subtracting the mean flipper length from each observation (otherwise known as centering) so that the zero value represents the average flipper length and the intercept represents the average body mass for the average flipper length.↩︎

Statistical inference is the process of drawing conclusions about a population (or an effect occurring in the real-world) based on sample data.↩︎

A model with \(\text{R}^2\) = 0.3 can still be incredibly useful if the effects are meaningful and the predictions are good enough for your purpose.↩︎

Fixing the problem can take many shapes. It could involve transforming the data to fit the model better, adding (or removing) variables that improve model fit, or fitting a different type of regression model entirely.↩︎